(Research findings) Anticipatory hope: Rohingya refugee teachers’ motivation to teach in Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh

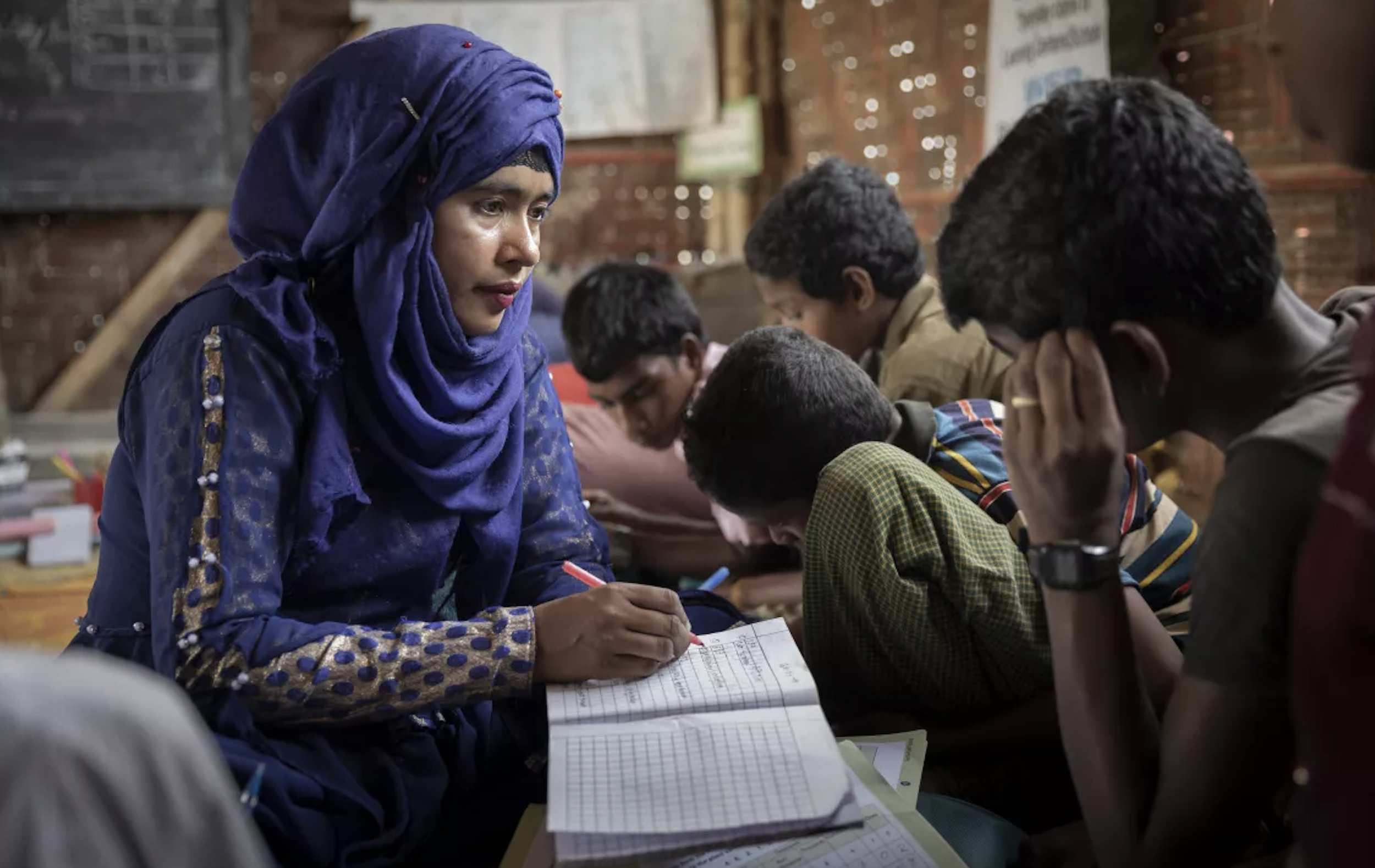

Note: This research summary is based on my doctoral dissertation fieldwork in Cox’s Bazar. Publications forthcoming. All names below have been anonymized to protect participant identities. Photo: UNICEF

Since the Myanmar military’s 2017 campaign of ethnic cleansing, more than one million Muslim minority Rohingya from Rakhine State have resided in the refugee camps of Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh. As of late 2024, over 6,000 learning facilities and 10,000 teachers from refugee- and host-community populations serve almost 400,000 Rohingya children and adolescents (ISCG, 2025). The purpose of refugee education in Cox’s Bazar is multifaceted due to the liminality of Rohingya displacement: It contributes to the protection of children’s rights and it creates a complicated sense of belonging via the Myanmar Curriculum and Burmese language, which are taught in anticipation of their possible repatriation to Myanmar.

Amid pronounced global teacher shortages (UNESCO, 2024), in settings like Cox’s Bazar United Nations agencies and international non-governmental organizations attribute the challenging conditions in which teachers work to a ‘teacher motivation crisis’. In parallel, the ‘global learning crisis’ sees teachers in such settings ‘deficit theorized’ by similar actors who often link teachers’ weak academic foundations, traditional teaching methods and need for professional development with children’s poor education outcomes (World Bank, 2019). In both instances, teachers’ propensity to be ‘alternatively qualified’ (Kirk and Winthrop, 2007) and ‘transformative intellectuals’ (Pherali et al., 2019) is overlooked, often rendering teachers as passive system inputs rather than empowered agents of change for their own children and communities.

To better understand this reality and its effects on Rohingya education, my doctoral study employed an explanatory sequential mixed-methods research design. It included a bespoke survey and follow-up focus group discussions to explain the community-, learning center-, and individual-level factors and experiences most associated with Rohingya refugee teachers’ motivation to teach.

Based on findings from a sample of 494 teachers representing Rohingya refugee and Bangladeshi host communities, to uphold teachers’ motivation to teach I recommend that humanitarian actors address a nuanced blend of extrinsic and intrinsic motivation factors via policy interventions that improve refugee teachers’ work conditions; namely: professional development; voice, agency, and sense of self-determination; and teacher safety and their experiences of well-being at work.

A plethora of motivation studies from high-income and stable contexts define teacher motivation and measure the influence of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation factors on teachers’ willingness to teach. Yet a dearth of evidence from low-income and fragile settings means our understanding of refugee teachers’ motivation to teach is based on anecdote more than empirical fact. My study in Cox’s Bazar, where Rohingya teachers live and work in overcrowded settings, receive inadequate pay, and experience heavy restrictions on their personal mobility, finds that intrinsic factors like a sense of self-efficacy and teacher agency and extrinsic factors like professional development and compensation are especially powerful motivators.

For Rohingya refugee teachers in particular, a political agenda focused on future repatriation to Myanmar—and education’s perceived role in achieving this goal—shapes their ‘anticipatory hope’ and underscores a stronger motivation to teach compared with their Bangladeshi host-community peers. Moreover, especially for Rohingya female teachers, the uncertainty of their displacement and long history of marginalization within their own community means the work of teaching has an elevating and transformative effect on their identities and lives, though not without concomitant risks.

As suggested by the ‘impossible fiction’ of refugee teachers’ work (Adelman, 2019) and the ‘parameters of hope’ that refugee education often represents (Dryden-Peterson and Reddick, 2017), there are practical, personal, and systemic limits to what education for the Rohingya in Cox’s Bazar can achieve. Complementing this reality, however, I find that ‘anticipatory hope’ defines Rohingya teachers’ core reason to continue teaching in such trying conditions. It affirms teaching’s fulfillment of normative and instrumental functions such as the right to quality education and a meaningful livelihood. But it also emphasizes the transformative function of teaching as an inherently human and political act: the work of teaching uplifts Rohingya identities, provides a tentative sense of belonging in Bangladesh and to Myanmar, and lays the groundwork for the repatriation that so many Rohingya hope will come.

Motivation to teach: High-level findings by teacher identity

Rohingya refugee teachers’ motivation to teach compared to Bangladeshi host-community teachers: Although the Rohingya teacher identity (n = 302) was significantly and positively more associated with specific motivation factors (e.g. self-efficacy and support) when compared with their Bangladeshi colleagues (n = 192), when all community-, learning center-, and individual-level motivation factors were regressed the Rohingya identity was marginally more associated with a motivation to teach, but not at a statistically significant level (β = 0.05).

Female teachers’ motivation to teach compared to male teachers: Across most motivation factors and at each level of analysis, female teachers from Rohingya and Bangladeshi communities (n = 204) had a consistently stronger association with the motivation to teach outcome factor than their male peers (n = 290). This was also true when all motivation factors were regressed together, with the female teacher identity having a positive and statistically more significant association with being motivated to teach (β = 0.10, p < 0.01).

Rohingya male teachers’ motivation to teach compared to all other identity groups: While the Rohingya male (n = 260) identity was more positively associated with a motivation to teach for specific motivation factors (e.g. respect and teacher agency) when all factors were regressed together Rohingya males had a marginal but statistically insignificant association with the motivation to teach outcome factor compared to all other identity groups (β = 0.06).

Rohingya female teachers’ motivation to teach compared to all other identity groups: Just over 80 percent of Rohingya female teachers (n = 41) reported a high level of motivation to teach. When all motivation factors and teacher identities were regressed together, the Rohingya female teacher identity was positively and significantly more associated with a motivation to teach (β = 0.11, p < 0.01) than their peers, representing the most positive association with a motivation to teach of all teacher identity groups.

The explanatory power of socio-ecological motivation factors on participants’ motivation to teach: An ordinary least squares regression analysis of participants’ demographic characteristics (identity, sex, age, teaching experience) on their motivation to teach explained only three percent (R = 0.03) of the variation in participant responses to the motivation to teach survey items. However, when the six socio-ecological motivation factors of respect, safety, support, work satisfaction, self-efficacy, and teacher agency were added to the regression, they contributed to 67 percent (R = 0.67) of the variance in participants’ motivation to teach. This shows that teachers’ respective experiences of motivation factors across the community-, learning center-, and individual-levels are a significantly more powerful predictor of a teachers’ motivation to teach than their demographic characteristics or identity alone.

Motivation to teach: High-level findings by socio-ecological level of analysis

At the community level: Of all motivation factors, participants’ experiences of community-level support (β = 0.20, p < 0.001) was the second-equal most powerful predictor of their motivation to teach. During times of disaster vulnerability or ration distribution in the camps, participant narratives revealed that community members were more likely to support teachers so they could continue teaching, compared to other members of the community.

“Suppose I am reconstructing my shelter, I am repairing my shelter. And as a teacher, then my … our community peoples help me voluntarily, for rebuilding my shelter or looking after my children while I teach.”

Anowar Monsur (Rohingya male, Camp C)

The next most significant predictor at the community level was participants’ sense of safety (β = 0.09, p < 0.01). While statistical analysis shows a positive association between feeling safe and being motivated, participant narratives revealed that the visibility of being a teacher means their safety is often at risk. This is due to armed gang violence and Bangladeshi security force harassment, which negatively impacts their motivation to continue teaching.

“Actually today, sir, we have nothing coming from our brain, because of last night. I could not sleep the whole of last night … armed groups have been shooting at each other … some of my students' shelters were destroyed by them.”

Mohammad Ullah (Rohingya male, Camp B)

The factor of respect (β = 0.01, non-significant) had a marginal and statistically insignificant association with participants’ motivation to teach. However, in focus group discussions participants noted the increased levels of respect they experienced since the implementation of the formal Myanmar curriculum, with some participants believing that community members now see them as ‘real teachers’. At the same time, participants problematized their experiences of respect, reiterating how their status makes them more susceptible to Rohingya armed gang violence and Bangladeshi security force harassment.

“... if they are going back, how can they contribute to their country? … For that reason the community members are now giving a lot more respect to the teachers who teach the Myanmar Curriculum.”

Somaya Akter (Rohingya female, Camp A)

At the learning center level: A sense of work satisfaction (β = 0.20, p < 0.001) is the second-equal most powerful predictor of participants’ motivation to teach, with Rohingya female teachers reporting the highest percentage of work satisfaction overall. While survey results showed that 58 percent of all participants experience a high level of work satisfaction, focus group discussions revealed nuanced experiences in relation to the Myanmar curriculum, the Burmese language, access to professional development, and workload stress, as described below.

• The Myanmar Curriculum was an overwhelmingly positive aspect of Rohingya participants’ work satisfaction, which Bangladeshi participants also reflected on. At the same time, many Rohingya males note the curriculum’s contribution to higher levels of workload stress.

“…it is their curriculum, their [country’s] language, their development. This is work satisfaction for them. So all Rohingya teachers are thinking, yes, this is good for us.”

Tosmin Ara (Bangladesh female, Camp A)

• Rohingya participants were generally positive about teaching the Burmese language, associating it with their strong agenda for repatriation. As stated below, however, it was also a source of considerable frustration and concern.

“... the Burmese language is stressful, not because it is the Burmese language, it is because we want to [teach] well and we cannot.”

Mohammad Ullah (Rohingya male, Camp B)

• Associated with the implementation of the Myanmar curriculum, participants experienced professional development as a ‘surrogate higher education’ which helped their motivation to teach. At the same time, many participants bemoaned a lack of alignment between available professional development and their stated pedagogical needs.

“... [Rohingya teachers] are saying ok, this is good … For their development, now they get many trainings, this helps their personal development.”

Hasina Rajuma (Bangladeshi female, Camp A)

• As the statement below illustrates, for some participants teaching offers a positive distraction from the stressors of displacement, poverty and violence within the camps. However, Rohingya male teachers in particular noted how the intersection of curriculum workload and safety concerns exacerbates their experiences of workload stress.

“Because she has the opportunity to teach, that makes her less stressed because she can earn money, she can provide. If she did not have any job or any work to do, that would make her more stressed… Other people in the camp, they are stressed because they have no income, because they have no education.”

Somaya Akter (Rohingya female, Camp A)

At the individual level: Of all motivation factors measured, a sense of self-efficacy (β = 0.34, p < 0.001) was the most positive and powerful predictor of participants’ motivation to teach. Moreover, there were interesting differences between Rohingya male and Rohingya female articulations of self-efficacy. For Rohingya females, self-efficacy is experienced via the sense of safety and belonging that they nurture with Rohingya children each day. For Rohingya males, however, a stronger sense of political purpose informs self-efficacy that will be realized once repatriation takes place. In other words, self-efficacy relates to a sense of preparedness.

“The way they are actually teaching in this community, they always feel [they provide] value of protection, the value of self, you know, the safety, security [for children], they know that very much … So that's why they have this confidence in their voices.”

Camp A translator, paraphrasing Rohingya females’ discussions on self-efficacy.

“I have lost everything in my life… my generation will not get an opportunity for a better future… I even lost myself … that is why I decide to teach for my children, for their generation.”

Sahidul Barua (Rohingya male, Camp B)

Participants’ sense of teacher agency (β = 0.10 p < 0.001) also has a powerful and positive association with their motivation to teach. However, focus group discussions revealed deep discontent among Rohingya males in particular. While they experienced high levels of pedagogical agency, they feel they have little self-determination in their profession and minimal influence on the Rohingya education system more broadly, at times revealing complex relations with the implementing partners that manage their learning centers and work.

The [implementing partner] is making the decision to teach all subjects, all the five subjects, but I think this is just cramming for the students… In one day, maybe we have to teach five subjects in a single shift, that is very difficult to cover … but we cannot reduce how much we teach … we cannot decide what we are going to do.

Manan Rahamot (Rohingya male, Camp D

Applying the ‘anticipatory hope’ of refugee teachers’ work to policy and practice

Recommendations to improve and maintain Rohingya refugee teachers’ motivation to teach in Cox’s Bazar include, but are not limited to:

1. Continue to invest in, protect, and normalize Rohingya female teachers’ work within the wider Rohingya community. Teaching’s impact on Rohingya females’ well-being is considerable with positive downstream effects on Rohingya girls.

2. Continue to invest in teacher protection and formal community support systems. For the purposes of professional identity and a sense of protection within the camps, consider the provision of teacher identity cards as this need was raised in all focus group discussions.

3. Prioritize teachers’ pedagogical skills and subject knowledge development. While assessment skills are important, many Rohingya teachers believed this is a ‘cart before the horse’ approach and that ‘causing learning’ and ‘classroom management’ should be the emphasis of professional development during the Myanmar curriculum rollout.

4. To reduce the workload disparities and the ‘cold conflict’ between refugee and host-community teachers, consider more formal contracts for Rohingya teachers in line with or near to what Bangladeshi teachers are afforded.

5. Consider further opportunities for Rohingya teacher career pathways, especially in terms of merit-based promotions within the learning center system beyond master trainer roles. This could include cluster management, Rohingya workforce leadership, and system governance responsibilities.

6. Provide opportunities for teachers’ inclusion in policy formation and decision-making processes, emphasizing a sense of individual agency and self-determination at the system level.